Deferrals from the Perspective of the User of Government Financial Statements

- Contributor

- Dean Michael Mead

Aug 1, 2023

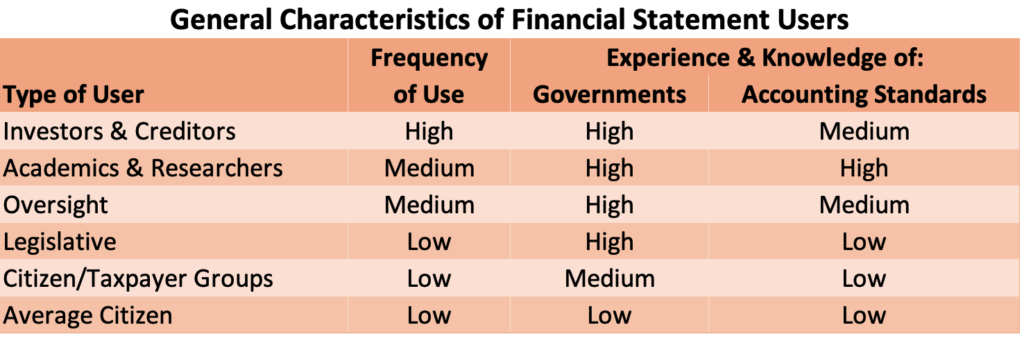

The audited financial statements of state and local governments are intended to communicate with a wide variety of people who analyze government financial health, make decisions about government finance, and hold governments accountable. Those “users” of financial statements have vastly different levels of experience and knowledge and are interested in a broad range of topics related to government finances. Despite those differences, they share a common need for reliable and relevant governmental financial information from audited financials.

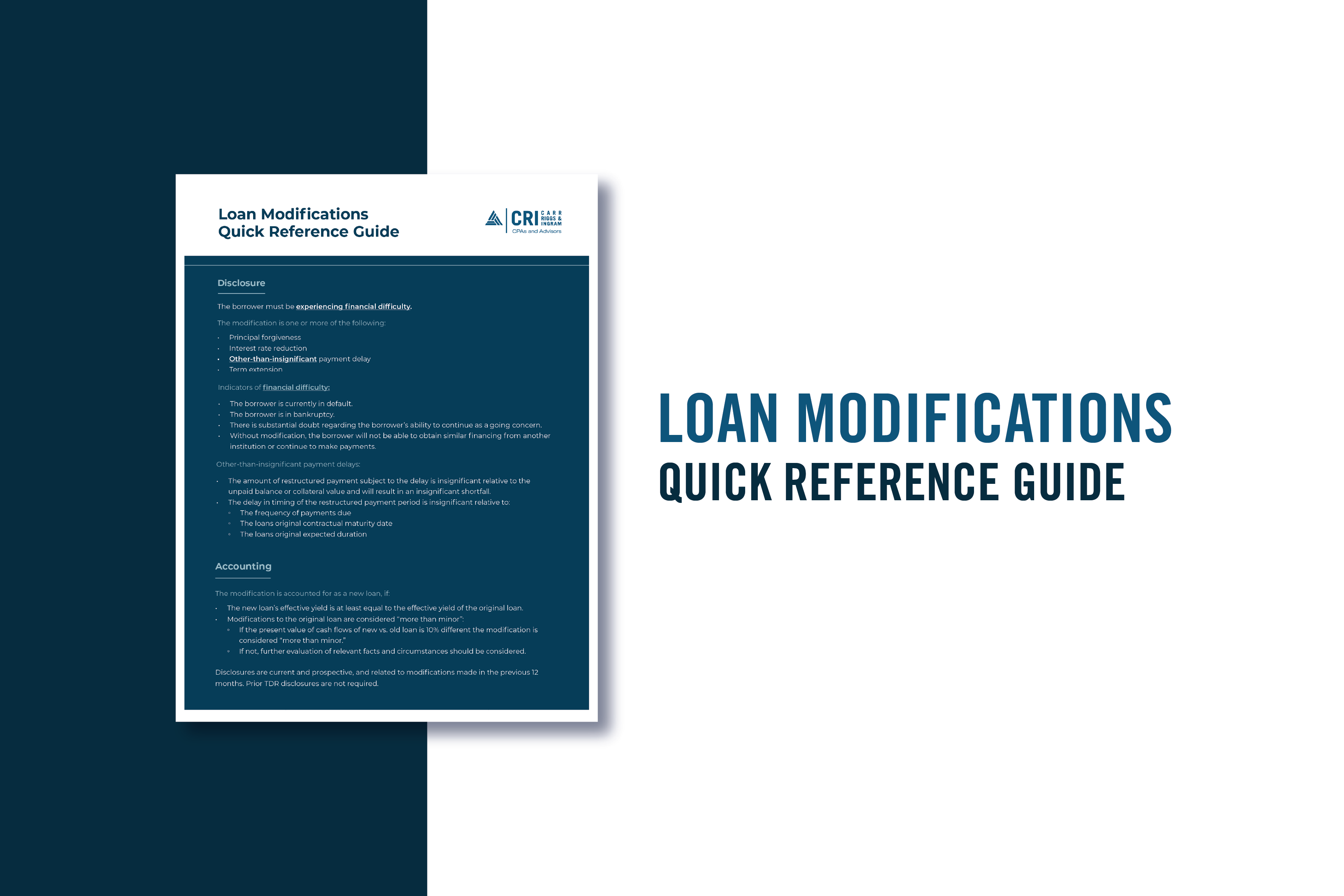

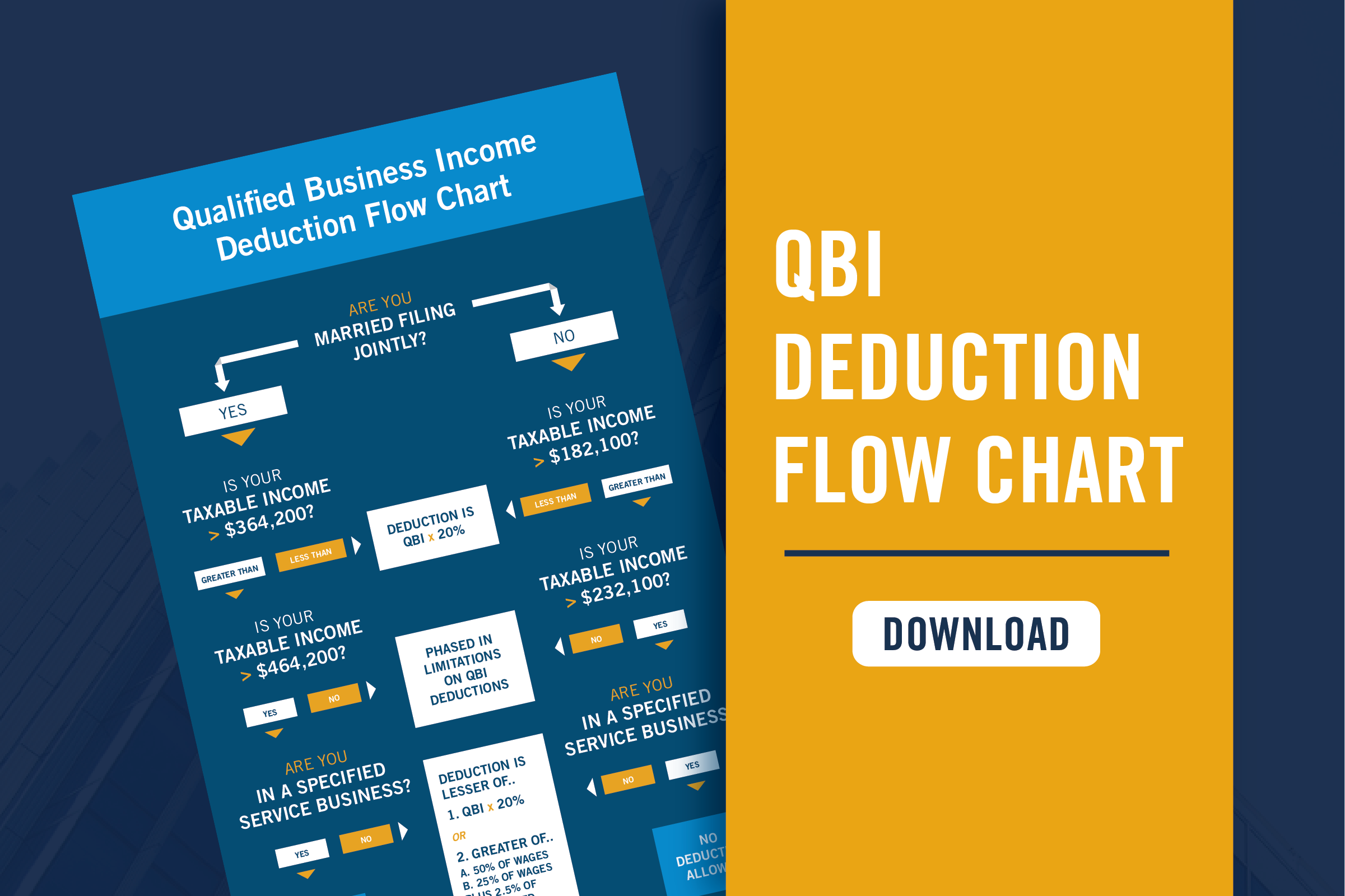

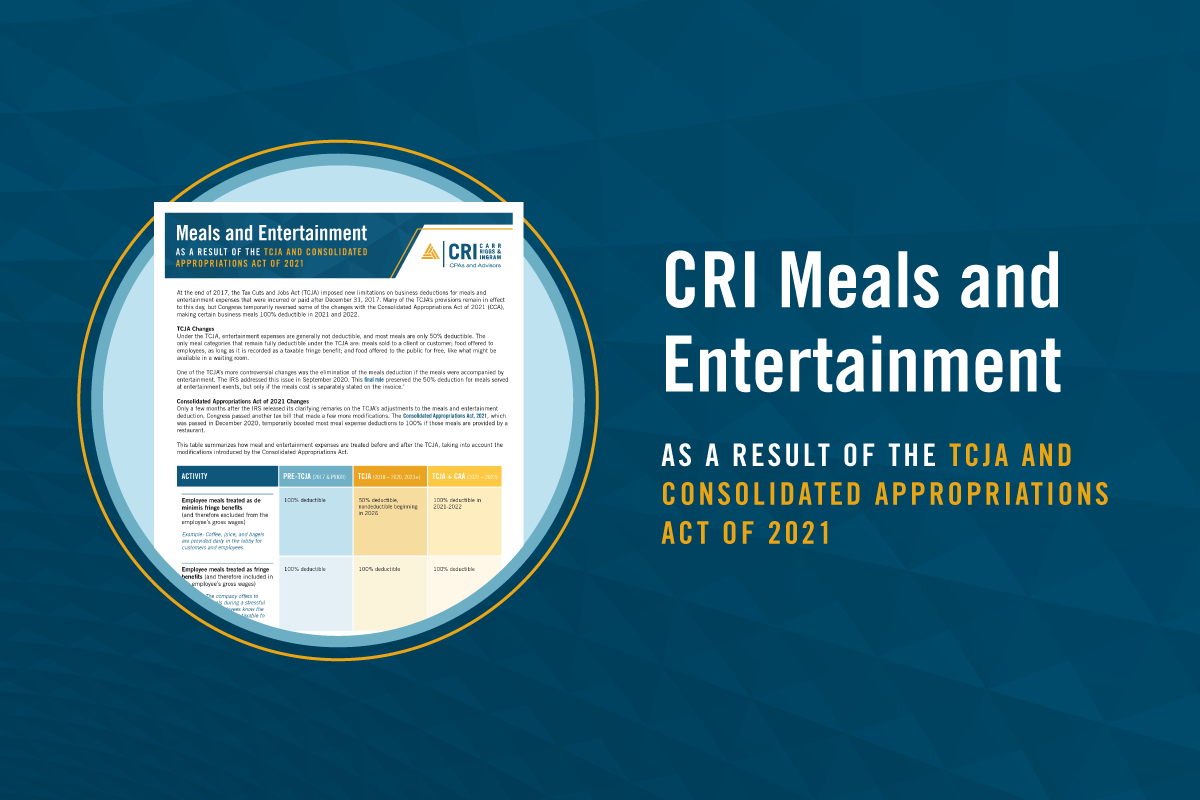

Another thing different types of users have in common—and in common with experienced auditors and government finance officers—is difficulty understanding two unique features of government financial statements: deferred outflows of resources and deferred inflows of resources (referred to as “deferrals”). To help the users, preparers, and auditors of financial statements to understand deferrals better, Carr, Riggs & Ingram CPAs and Advisors have developed free plain-language resources that include:

- Webinar recording and slide deck, “Demystifying Deferrals”

- Short plain-language article, “Deferred Outflows and Deferred Inflows of Resources in a Nutshell”

- Longer plain-language article, “Demystifying Deferrals: What They Are, What They Mean, and Why They Are Important”

- Podcast: It Figures, Season 4, Episode 14, “Demystifying Deferrals” on the top-5 issues with deferrals

- E-book containing text, short videos, discussion questions and exercises, and links to the other resources

- Technical slide deck for those who want to dig into the accounting standards, including debits and credits.

Those resources are informative about what deferrals are, where they came from, why they are important, and what they say about a government’s finances. This article complements those resources by focusing specifically on what deferrals communicate to users and how deferrals information can play a role in their analyses, decisions, and accountability—with as much plain language and as little technical jargon as possible.

Users in a Nutshell

As “general purpose” financial statements, the audited financials that governments issue based on generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) as published by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) theoretically should be usable by and understandable to both seasoned technical experts and neophyte average citizens, and to the many kinds of people in between. No matter their prior knowledge or experience, a person who (1) has an interest in government finance and a need for information and (2) is willing to invest a reasonable amount of time in getting up to speed on government accounting basics and reading the financial report, should be able to use financial statement information meaningfully.

Conceptually, users are categorized by the GASB as investors and creditors, oversight and legislative, and the citizenry.

Investors and Creditors

Investors and creditors play crucial roles in supporting governments by participating in the sale and purchase of municipal bonds and notes, as well as extending loans and providing goods and services on credit. Analysts at those entities generally evaluate a government’s “creditworthiness”—its ability to repay its debts on time. Rating agency analysts evaluate creditworthiness and assign governments “credit ratings” based on that analysis. Analysts at other companies evaluate creditworthiness to inform decisions about, among other purposes:

- Whether to buy a government’s bonds as investments

- Whether to hold those bonds or subsequently sell them (and at what price)

- Whether to “underwrite” or insure a government’s bonds and how much to charge for those services, and

- Whether to allow a government to purchase goods or services on account and in what amounts.

As frequent and intensive readers of financial statements, those users are very familiar with the information they contain and understand the underlying accounting rules better than most users.

Legislative and Oversight

Users in the governing bodies of states, counties, cities, and other governments are elected officials and their staff. Users in oversight organizations are staff at governmental entities that keep an eye on or regulate the finances of other governments, such as state education departments and state-appointed fiscal monitors. Elected legislators and their staff are particularly interested in allocating a government’s tax revenues and other scarce resources among competing public services through the budget process. They subsequently need to monitor actual experience against the budget and ensure that revenues and expenditures are balanced for the year. They also perform oversight functions, along with dedicated oversight agencies and commissions, through which they seek to hold their and other governments accountable for the effective and efficient use of public monies. Legislative users are generally knowledgeable about governments and government finances and are familiar with government accounting rather than knowledgeable about it. Oversight users have a comparable degree of knowledge about governments and are generally knowledgeable about accounting standards as well.

Average Citizens

The citizenry, comprising the largest group of potential users, often lacks knowledge about government accounting and is less likely to utilize government financial reports directly. However, staff at citizen groups and taxpayer associations, who are studying and reporting publicly on issues that are important to citizens, may have a basic knowledge of government accounting as necessary to understand those issues and report on them to the public. Similar to legislative and oversight users, a common interest of citizen users is holding governments accountable for the effective and efficient use of limited public resources.

Academics and Researchers

A fourth user category might include professors in colleges and universities who teach or conduct research on topics related to government finance, as well as people conducting research on such topics at think tanks and public policy groups. They may be knowledgeable about governmental accounting and generally are knowledgeable about governments and the governmental financial environment.

Shared Interests

Differences in experience, knowledge, and primary focuses notwithstanding, the various kinds of users share some concerns about governments and need information about the same aspects of government finance. For example, information about a government’s level of indebtedness is potentially significant to all user types. However, the nature of their concern may diverge because of the different purposes for which they utilize the information. A legislative or oversight user may focus on how close the amount of outstanding debt is to the government’s state-imposed debt limit to ensure the limit is not exceeded or to assess available legal borrowing authority to finance necessary infrastructure investments. A citizen group may concentrate on the government’s debt burden, the cost of repaying it, and the resulting property tax bills. A municipal bond analyst may evaluate the amount of outstanding debt in the context of the government’s financial capacity to repay existing debt and to afford to issue additional debt.

Similarly, the various types of users often compare annual revenues with annual expenses or expenditures. Municipal bond analysts may view a government that raises enough revenue each year to cover its expenses as more creditworthy, all other factors being equal, than a government that spends more than it takes in and covers the difference by draining its reserves or pushing costs off to the future. Legislative and oversight users may be monitoring whether the government achieved actual budget balance for the year. Citizen groups may be attentive to budget balance, in addition to holding the government accounting for “making ends meet” or “living within its means” each year, a concept the GASB calls interperiod equity.

How Deferrals Inform Users’ Shared Interests

The information about deferrals in government financial statements is important to both of those common interests.

Government Indebtedness

Appropriately evaluating a government’s degree of indebtedness depends in part on having accurate information about its liabilities (and assets, too). Some debt indicators are limited to bonds, notes, and loans, while some are more broadly inclusive of other amounts owed. These may include liabilities related to pensions, retiree health insurance (also known as other post-employment benefits or OPEB), long-term leases, accrued vacation and sick leave to be paid upon retirement, claims and settlements, and costs associated with landfill closure.

One of the essential consequences of the introduction of deferrals to government financial statements was the reclassification of things that previously were reported as assets or liabilities but were not actually resources owned amounts owed. Before the GASB required those items to be reported as deferred outflows of resources and deferred inflows of resources, they generally were indistinguishable from other assets and liabilities. The result was potentially overstated assets and liabilities, which could lead to inaccurately calculated indebtedness indicators, leading to mistaken conclusions about a government’s ability to repay existing liabilities or to incur additional liabilities. In many cases, users were unaware they were incorporating faulty information into their analyses, decision-making, and accountability efforts.

Consider how the following typical indicators of indebtedness were affected before deferrals were removed from the assets and liabilities:

| Indicator | Potential Negative Effect on Government |

|---|---|

| Liabilities ÷ population | Appears more indebted than it really is |

| Liabilities ÷ assets | Could appear more or less indebted than it really is |

| Liabilities ÷ net assets (or fund balance) | Could appear more or less indebted than it really is |

| Liabilities ÷ expenses (or expenditures) | Appears more indebted than it really is |

| Liabilities ÷ assessed property values | Appears more indebted than it really is |

In the time before deferrals, no “liability” was more notorious than “deferred revenues.” In a typical government’s governmental funds, the amounts reported as deferred revenues liabilities may have included amounts owed to others (customer fees and grants received in advance) and amounts waiting to be reported as revenues (grants with time restrictions and unavailable revenue).

Customer fees received before services are provided appropriately are reported as a liability because, if the government doesn’t provide the service, the money must be returned to the customer. The same can be said if a government never meets the eligibility requirements for grants it received in advance. On the other hand, grants with time restrictions but no further eligibility requirements aren’t owed to anyone; a government just needs to wait until the year when it is allowed to spend them. Lastly, unavailable revenue is a product of the modified accrual basis of accounting in the governmental funds. Rather than an amount owed, unavailable revenue represents amounts due to the government that were not collected during the year or soon enough after fiscal year-end to be used to pay this fiscal year’s expenditures—consequently, it was not reported as revenue in the governmental funds.

It used to be common that deferred revenue was one of the larger liabilities in the governmental funds. To the extent that it contained items that were not really amounts owed, it caused total liabilities to be overstated and made a government look worse off financially, all other factors being equal. Compounding that problem, it was also common that unavailable revenue was the largest component of deferred revenue, sometimes larger than the other parts of deferred revenue combined.

The financial statements are more accurate as a result of reporting deferrals—rather than assets and liabilities—for grants with time restrictions, unavailable revenue, and other items that are not resources owned or amounts owed. Financial statements after the introduction of deferrals better inform users’ analyses, decisions, and accountability efforts.

Take a deeper dive:

See the sections “Misidentifying assets and liabilities” and “Accuracy of financial ratios” in the longer plain-language article

See slides 37–39, 50, 51, 74, and 79 in the webinar slide deck

Comparing Revenues and Expenses (Expenditures)

Imagine that a city hires a company to build a public sports and entertainment venue and operate it on the city’s behalf for 25 years. As part of the deal, the company pays the city $50 million when the contract is signed, before construction has even begun. The decision about when that up-front payment should be reported by the city as revenue will directly affect a users’ analyses, decisions, and assessments of accountability related to the city’s finances.

If the entire $50 million is reported at once—for example, in the year when the contract is signed or in first of the 25 years the company operates the facility—revenues may look substantially greater than expenses in that year but be unaffected in the rest of the years of the arrangement. From a user’s perspective, would that be an accurate depiction of the city’s interperiod equity—whether it is making ends meet in each of next 25 or more years?

GASB standards view the $50 million up-front payment as part of the compensation the company is paying the city for the right to operate the venue (and, conceivably, to collect revenue of its own by doing so). Even though the city received the money all at once, it is “earning” the money over the 25 years during which the company has the right to operate the venue. That argues for reporting the up-front payment as revenue over the 25-year period, as the city earns it. When it receives the $50 million, it reports the cash and a deferred inflow of resources in that amount. It then reports the revenue in each of the 25 years, likely in equal amounts of $2 million, and reduces the deferral by the same amount.

Viewing the two graphs— (A) reflecting reporting the payment as revenue in a lump sum and the right (B) reflecting reporting revenue in equal annual installments—illustrates how reporting the revenue all at once would distort comparisons of annual revenue and expenses.

A user examining the information in (A) might interpret the larger-than-usual cash inflow in 2023 from the up-front payment as an extraordinarily good financial performance. With seven additional years of revenue and expense information for 2024–2030, we can see that it was a one-time occurrence. However, a user in 2024 who is first seeing the audited financial statements for 2023 does not benefit from that hindsight. To them, it may seem like the government’s financial fortunes have greatly improved, and they may base analytical conclusions or decisions on that perception. A credit officer at a bank may conclude that the government has a greater capacity to repay its loans or to take out additional loans. A county legislator or a taxpayer association member may believe their county can afford to expand services, add new programs, or cut tax rates.

Deferrals play a similar role in other multiyear transactions, ensuring that revenue is appropriately assigned to the years in which it is earned, regardless of when cash changes hands or when a government reports a long-term receivable. For instance, when a government signs a contract as a lessor, leasing public facilities to companies or not-for-profit organizations for multiple years, it can record a receivable for the payments it will receive over the lease term. Rather than record an equivalent amount of lease revenue simultaneously, the government initially reports a deferred inflow and then reports revenue annually during the lease term, reducing the deferral simultaneously.

Take a deeper dive:

- See the sections “Leases,” “Why Are Deferrals Important?” and “Interperiod equity” in the longer plain-language article

- See slides 43–46 and 89 in the webinar slide deck

Other Uses of Deferral Information

Deferral information is valuable to users for purposes beyond calculating accurate financial ratios and evaluating interperiod equity. Broadly, deferral information is useful and relevant in any circumstance in which it is important that revenues and expenses/expenditures be reported in the correct years and in the correct amounts.

Take a deeper dive:

See slides 28, 34, and 57 in the webinar slide deck

For example, several types of deferrals relate to governments’ liabilities for pensions and OPEB and are useful for understanding why those liabilities increase or decrease over time and how it will impact future expenses.

Take a deeper dive:

- See the sections “Pension and OPEB liabilities” and “Trends in future pension and OPEB expenses” in the longer plain-language article

- See slides 52–55, 60, and 83–85 in the webinar slide deck

Comparisons of deferrals for unavailable revenue with the related amounts receivable—such as unavailable revenue–grants and grants receivable—provide insights into a government’s ability to collect amounts it is owed and whether that ability has improved or deteriorated.

Take a deeper dive:

- See the section “Ability to collect receivables” in the longer plain-language article

- See slides 80 and 81 in the webinar slide deck

Notes to financial statements disclose deferral balances related to transactions called “hedging derivative instruments.” That information is valuable for assessing the risk that a government will have to make a substantial payment to the bank or other party in the transaction should a hedging derivative instrument with a sizeable deferred outflow balance terminate unexpectedly.

Take a deeper dive:

- See slides 58, 59, and 87 in the webinar slide deck